Byzantine Emperor of Trebizond

Sam Topalidis (2024)

Pontic Historian and Ethnologist

Introduction

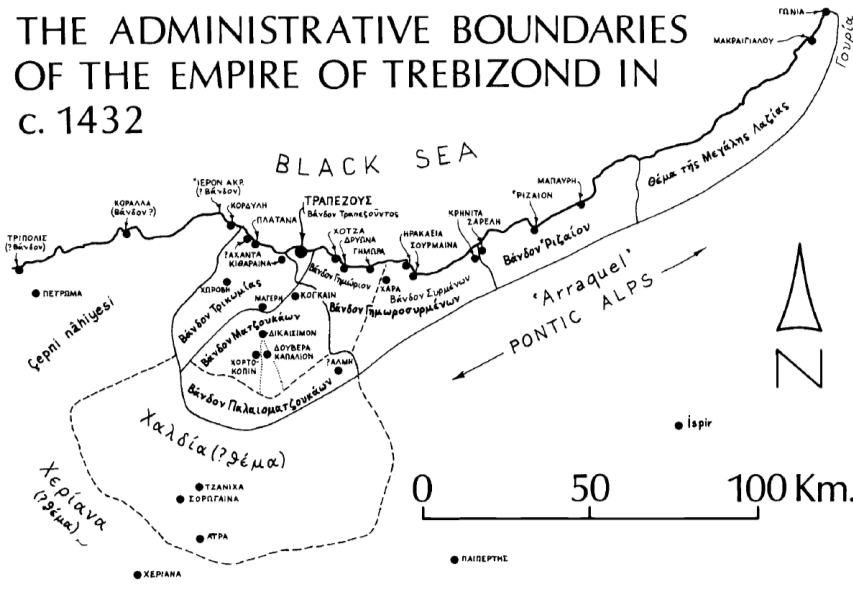

Alexios IV Grand Komnenos (reign 1417–1429) was the emperor of the small Byzantine empire of Trebizond in north-east Anatolia near the Black Sea (Fig. 1). Details of his life and the discovery and movement of what are believed to be his remains will be addressed here.

Fig. 1: The Byzantine Trebizond empire c. 1432 (in Greek) (TPAΠEZOYΣ is Trabzon, Bryer and Winfield 1985:ii).

Establishment of the Komnenoi Kingdom

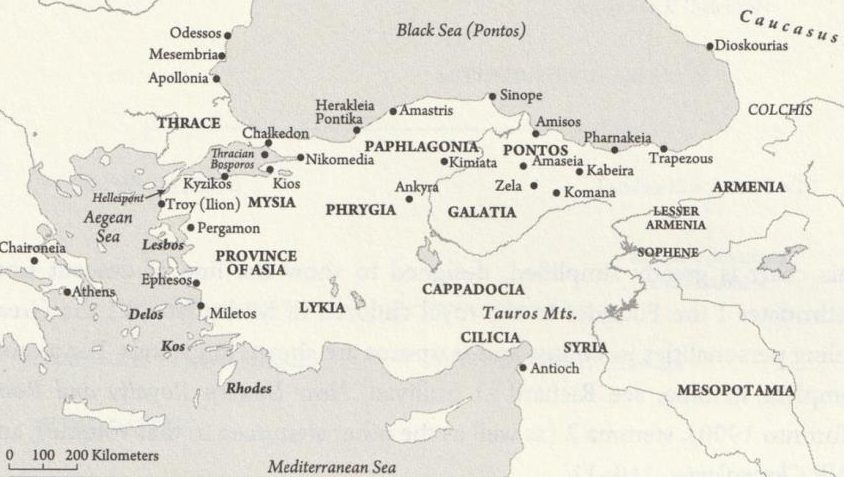

In 1204, just before Constantinople fell during the Fourth Crusade, Alexios and David Komnenos, the grandsons of the Byzantine [Eastern Roman] emperor Andronikos I, left Constantinople for Georgia. In the same year, with soldiers provided by their aunt queen Thamar of Georgia, they occupied Trabzon on the Black Sea coast (Trapezous in Fig. 2) (Miller 1926). From there, the small Komnenoi empire of Trebizond (1204–1461) became an independent state separate from Constantinople.

Alexios IV Komnenos

Alexios was born in Trabzon, probably about 1381, the son of Manuel III Grand Komnenos (reign 1390–1417) and Eudokia, daughter of the king of the king of Georgia. When his mother died in 1395, his father sent a relative to Constantinople to seek a bride for himself and for his son

Fig. 2: Anatolia (Roller 2020: xi).

Alexios. In September 1395, two brides, Anna Philanthropene for Manuel III and Theodora Kantakouzene for Alexios arrived in Trabzon. Alexios IV was co-emperor for over 22 years until 1417, when his father the emperor died. In turn Alexios’ son, John, was also co-emperor with his father in the 12 years before Alexios IV was assassinated in 1429 (Bryer 1984:315).

Alexios married Theodora Kantakouzene, with whom he had [at least] four daughtersand three sons: Alexander and the future emperors John IV (1429–1458) and David (1458–1461).[1] The names of his daughters remain unknown, except Maria, who became wife of the Byzantine emperor at Constantinople while Irene, married the Serbian despot Durad Brancović (asiaminor.ehw.gr/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=7173).

Alexios IV was the benefactor of many monasteries and churches. In 1427, he built the tower in the courtyard of the monastery of Hagia Sophia in Trabzon and restored the monastery of St George Peristereota (south of Trabzon in Maçka); he also gave land to the monastery of the Panagia of Pharos[2] (asiaminor.ehw.gr/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=7173).

During his reign, Alexios IV was confronted by the Genoese, who were fighting an economic war with his empire. Alexios signed a treaty in 1418 and paid compensation for the destruction of Genoese possessions within his empire. In his diplomatic relations with Muslim and Christian rulers, Alexios IV managed to secure his empire against external threats, by continuing his grandfather’s wise policy of marriages between other rulers and the female members of the dynasty of Grand Komnenoi (who were renowned for their beauty). He allied himself through marriage with two Turcoman rulers, with the Serbian despot and with the Byzantine emperor at Constantinople. Alexios IV was brutally murdered by followers of his son John, who did not follow John’s orders. John IV was crowned emperor and he severely punished his father’s murderers[3] (asiaminor.ehw.gr/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=7173).

Discovery of Alexios IV’s Remains[4]

From April 1916 to February 1918, during World War I, the Russian army occupied north-east Anatolia, including the Trabzon area. In the summers of 1916 and 1917, the Russian Academy of Sciences sent expeditions to the Trabzon region under Professor Uspenskii’s leadership in order to guard, register and describe local historic monuments and artefacts (Tsypkina 2019).

The Chrysokephalos church, built in the 10th century within the Trabzon walls and converted into a mosque in 1461, seems to have been the imperial burial place of the Komnenos Byzantine emperors of Trebizond. The only tomb which appears to have survived in modern times stood about 10 m from the church (Plate 1).[5] It consisted of a canopy supported by four columns in a 4 m to 5 m square, supporting open round arches (Bryer and Winfield 1985:201). Morozov and the 71 year old Uspenskii excavated this tomb (in September 1916) and found a decapitated skeleton in a violated and broken sarcophagus as well as a second skeleton of a youth lying above it. Mintslov recorded that the skull of the upper interred person had a suture running from the brow to the top of the head. The lower skull (believed to be that of Alexios IV) was long and similar to the skull that Mintslov had found in the nearby former church of St Eugenios (Mintslov 1923:129–130).

Laonikos Chalkokondyles (c. 1430–c. 1465) states that John IV had his father, emperor Alexios IV buried initially in the Theoskepastos monastery on Boztepe in Trabzon and later moved to the Chrysokephalos church. Evidently, John IV wanted to make a public show of remorse for the death of his father; on this basis, Uspenskii believed that the decapitated skeleton found within the tomb was that of Alexios IV since the skeleton was of a man who had died violently and been assigned a splendid memorial. Later, an Ottoman tale claimed that the tomb was apparently reused for a youth called Hoşoğlan (Bryer and Winfield 1985:201).[6]

Plate 1: Uspenskii (on the left) and Morozov at the Alexios IV covered tomb at the Chrysokephalos church 1916 (Chrysanthos 1933:927).

The skeleton of Alexios IV [if indeed it is Alexios IV] was entrusted to Chrysanthos, Greek metropolitan of the metropolitanate of Trabzon[7], who in 1918 reinterred it in the St Gregory of Nyssa Greek metropolitan church of Trabzon. The covered tomb of Alexios at the Chrysokephalos church was destroyed after 1918. Professor Bryer could not trace what happened to the remains ascribed to Hoşoğlan. Şakir (1877), in a work unknown to Uspenskii, stated that the tomb of [the alleged] Hoşoğlan and Alexios IV had been reopened in 1842. Only a skull of a young man was found (Bryer 1984:325–327). Kennedy (2021) hypothesised that the bones, believed to be of Alexios IV, St Eugenios [which Mintslov unearthed in the former St Eugenios church in Trabzon] and Hoşoğlan were mixed up.

During the compulsory Exchange of Populations between Greece and Türkiye in the early 1920s, when Christians left Turkish territories for Greece (and Muslims from Greece moved to Türkiye), George Kandilaptis salvaged the remains of Alexios IV [Chrysanthos had earlier left Trabzon] and brought them to the Byzantine Museum in Athens. In 1980, the remains of Alexios IV were taken with much ceremony by Pontic Greek organisations to a final resting place in the New Soumela monastery in the village of Kastania near Veria in northern Greece (Plates 2–3) (Bryer 1984). This monastery also holds the famous Panagia Soumela icon from the Soumela monastery in Maçka, south of Trabzon.

Plate 2: P Lazarides, Director of the Byzantine Museum, Athens carrying out the remains of Alexios IV (1980 photo by Athena Kalliga, Bryer 1984:340).

Plate 3: The reinternment of the remains of Alexios IV at the New Soumela monastery near Veria in northern Greece, 1980. The remains are carried behind the Pontic flag (Bryer 1984:340).

Conclusion

Grand Komnenos Alexios IV (reign 1417–1429) maintained his small Byzantine empire against external threats by marrying four female family members to other rulers. During his reign, he was the benefactor of churches and monasteries including the Hagia Sophia monastery in Trabzon and the St George Peristereota monastery in Maçka, south of Trabzon.

He was brutally murdered and his remains (if they are indeed his) are the only surviving remains of any Trebizond Byzantine emperor (1204–1461). They now rest in the New Soumela monastery near Veria in northern Greece which also holds the famous Panagia Soumela icon from the Soumela monastery from Maçka.

Acknowledgements

I warmly thank Russell McCaskie for his comments.

References

Bryer A (1984) ‘“The faithless Kabazitai and Scholarioi’”, in Moffatt A (ed) Maistor: Classical, Byzantine and Renaissance Studies for Robert Browning (Byzantina Australiensia), 5:309–327, Canberra.

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Chalkokondyles L The histories, I and II (Kaldellis A trans in 2014), Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, USA.

Chrysanthos (1933) ‘H Eκκλησια Τραπεζουντος’, (in Katharevousa Greek), [The church of Trabzon] Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], iv-v, Athens.

Kennedy S (2021) ‘A tale of two skeletons? Greco-Turkish cultural memory, sacred space, and the mystery of the identity of the occupants of a now lost ciborium Byzantine tomb at Trebizond’, Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 114(1):195–220.

Kiminas D (2009) The Ecumenical Patriarchate: a history of its Metropolitanates with annotated hierarch catalogs, Orthodox Christianity, I, The Borgo Press, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Miller W (1926) Trebizond: the last Greek empire, The MacMillan Co, London.

Mintslov SR (1923) Trapezondskaia epopeia (in Russian), [Trabzon epic], Sibirskoe Knigoizdatel’stvo, Berlin.

Roller DW (2020) Empire of the Black Sea: the rise and fall of the Mithridatic world, Oxford University Press, New York.

Şakir S (1877) Trabzon Tarihi, in Turkish [Trabzon history], Umran Matbaasi, Istanbul.

Topalidis S and McCaskie R (2022) ‘Fedor Uspenskii’s archaeological research in Trabzon during World War I, Archeion Pontou, [Archives of Pontos] 62:200–219.

Tsypkina AG (2019) ‘Opisanie rukopisei Trapezundskoi ekspeditsiei letom 1917 g’ (in Russian) [‘A description of manuscripts of the Trabzon expedition in the summer of 1917’], Vostok, 4:208–219.

[1] David was the last Byzantine emperor of Trebizond. In 1461, he surrendered Trabzon to the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II.

[2] Located on the little headland near the Hagia Sophia monastery.

[3] His instructions were not to kill Alexios IV but to bring him to John. He punished his father’s murderers by blinding one and cutting the hands off the other (Chalkokondyles).

[4] More details can be found in Topalidis and McCaskie (2022).

[5] Tombs of other Grand Komnenoi within the Chrysokephalos church were probably destroyed when the church was converted into a mosque in 1461 (Bryer 1984: 325).

[6] Kennedy (2021) describes how tales about Hoşoğlan may have been created by the Ottoman Turks. Kennedy speculates that both skeletons excavated from the former Chrysokephalos church were Trabzon Byzantine emperors. We may never know.

[7] The metropolitanate of Trabzon extended around 280 km along the Black Sea coast (Kiminas 2009).