Sam Topalidis (Pontic Historian) 2024

Introduction

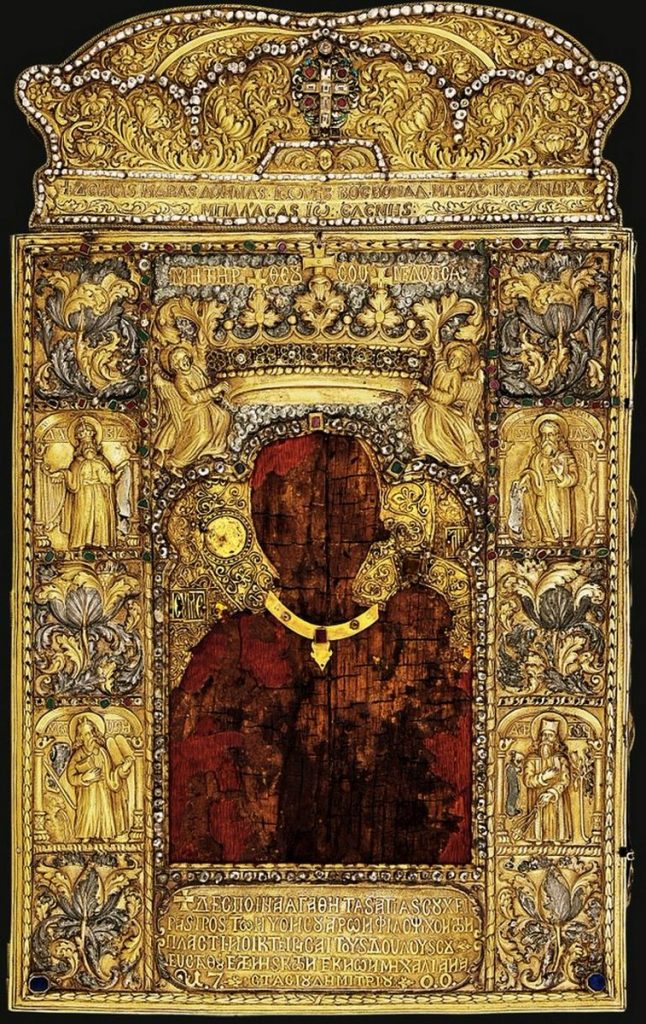

The Soumela monastery and the icon of Panagia Soumela (Plate 1) are extremely important symbols of Pontic Greek identity and are highly revered. Today, the monastery is one of the most important tourist destinations in the Trabzon region of north-eastern Türkiye.

Plate 1: Panagia Soumela icon (https://twitter.com/TempusFugit4016/status/1714476808710570456)

The former Greek Orthodox monastery of the Virgin Mary, Soumela (Plates 2–3) is 50 km south of Trabzon. The monastery is perched on the cliff face of Karadağ (Mount Mela), nearly 300 m above the west bank of a tributary of the Degirmen Dere (Mill River). The monastery complex has five floors and 72 rooms and is apparently built of volcanic andesite, trachyte and travertine limestone and bricks (Nuhoglu et al. 2017).

Plate 2: Soumela monastery

The monastery was probably founded by the 10th century and it was abandoned in 1923, after the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

In 1461, when the Ottoman sultan Mehmet II captured Trabzon from the Byzantine Komnenoi Trebizond emperors, the three great monasteries of Peristereota, Soumela and Vazelon, retained their holdings in their neighbourhood in the Matzoukan valley (Lowry 1991:279).

The establishment of the small Greek Orthodox metropolitanate of Rhodopolis[1] in 1863 encompassed these three monasteries. In 1864, the monastic approach, the aqueduct, the library and the façade were built. They also replaced the old wooden cells which had hung from the cliff face. In late 1877, the monastery was robbed by a Turkish gang. Thankfully they did not take the Soumela icon (Bryer and Winfield (1970); (1985)).

Plate 3: Courtyard of Soumela monastery, 1915 (Chrysanthos 1933:984).

Closure of Soumela Monastery and Recovery of the Icon

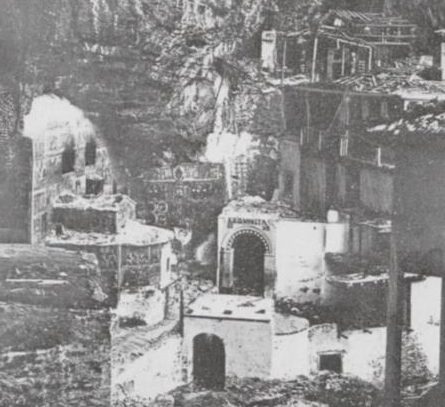

In late 1922, Jeremias Tsaridis [the last abbot][2] and monks Panayiotis Stefanidis and Polykarpos Parmaxous placed the Soumela icon, the manuscript of the gospel of St Christopher and the Cross of the Trebizond emperor Manuel III Komnenos in a chest which they buried in the nearby chapel of St Barbara. In February 1923, the monks were attacked by people who were intent on stealing the monastery’s treasures. The monks were made to leave the monastery, leaving their belongings behind. They walked to Trabzon and then Ottoman soldiers forced them to leave the port (Tanimanidis 2020:113–114). After the monastery was abandoned, it was gutted by a fire in or before 1929. It suffered badly from vandals (Plate 4) (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

In 1931, Greece was allowed to retrieve the monastery’s hidden treasures. In late October, Ambrosios, one of the former monks of Soumela, after receiving instruction from former abbot Jeremias as to where the treasures were buried, set out for Soumela. After extracting the items from the former St Barbara church, Ambrosios returned to Athens and provided the items to Chrysanthos who deposited them with the Benaki Museum. Finally in 1950, when Pontic Greeks had built a new church to Panayia Soumela at the village of Kastania (between Kozani and Veria) in northern Greece, the icon was placed in this new church on 15 August 1952 (Holy Apostles Convent 1991:78–83).

Plate 4: Courtyard in the Soumela monastery (1929 Talbot Rice (Bryer and Winfield (1985, plate 209)).

In 1961, the Soumela monastery became the headquarters of a State Experimental Forest (Turkey) and Soumela[3] survives today largely due to the efforts of Şϋkrϋ Köse, its first Chief Ranger (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

The remainder of this document will focus on the observations by the following foreign travellers to Soumela:

- Joseph Pitton de Tournefort 1701, Chief Botanist to the French king

- George Finlay 1850, Scottish historian

- Reverend Henry Tozer 1879, British writer

- Sergei Mintslov 1916, Russian soldier and author

- David Talbot Rice[4] 1929, English Professor of Art History.

These accounts vary in detail but collectively, are a wonderful testimony to the scale and impressive nature of the structures and the awe and wonderment its many visitors over the centuries experienced on visiting the monastery and its environs.

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort

Frenchman, Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656–1708), chief botanist to king Louis XIV of France, visited the Soumela monastery in 1701. Tournefort fell in love with the area. It is believed that he was describing the Soumela monastery in this translation of his writings.

Finer Forests are not among the Alps. The Mountains round this Convent produce Beech-trees, Oaks, Yoke-Elms, Guaiacs, Ash and Fir-trees of a prodigious Height. The House of the Religious is built of nothing but Wood, close against a very steep Rock, at the bottom of the finest Solitude in the World. The View of this Convent is bounded by nothing but the most charming Prospects; and I could gladly here have spent the rest of my Days. … not one of these Monks is in the least affected with all this, tho there are about forty of them. … These Hermits possess all the Country for about six miles about. They have several Farms among these Mountains and a good many Houses even in Trebisond (Tournefort 1741:72–74).

George Finlay

Scottish historian, George Finlay (1799–1875), spent much of his life in Greece. Finlay gives a glimpse of his visit to the Soumela monastery in his unpublished diary of June 1850. He confided it is impossible not to be in ecstasy with such scenery:

Our letter from the Bishop being duly examined we were admitted and led first to the church where the holy picture painted [as legend states] by St Luke was taken from its case & placed in our hands to kiss & we threatened with a mass to welcome (us) … The roar of the waters … below the monastery, the snowy slopes visible on the ridge to the south over the valley which (is) hardly a rifle-shot across, the immense wooden pile of buildings with its galleries & cells clinging like swallows’ nests to the precipice, the sound of the convent bell continually announcing the arrival of parties of pilgrims and the nasal chant of the continual masses was grand, strange, solemn and picturesque. We had a careful examination of the caverned church … the Abbot spoke Turkish better than Greek … [because he spoke Romeyka Greek, not demotic Greek] (Bryer and Winfield 1970:274–275).

Henry Tozer

In 1879, Reverend Henry Fanshawe Tozer (1829–1916), British writer, traveller, teacher and geographer described his first vision of Soumela.

What followed appeared to us like a fairy scene … Here a perpendicular cliff rises to the height of nearly a thousand feet and in the very middle of the face of this, in the hollow of a cavern, stands the monastery, its white buildings offering a marked contrast to the brown rock, which seems to form their setting. The first feeling to the beholder is one of amazement that any human being should have established themselves in a place apparently so inaccessible (Tozer 1881:435).

From the spot where we were now standing fifty stone steps have been constructed, reaching to the summit of this buttress and thence again a wooden staircase descends an equal distance on the further side into the monastery. The actual gateway is at the top of the flight of steps … To describe the appearance of the interior of the monastery is an almost impossible task, owing to the absence of an almost uniformity in the buildings, some being of wood and some of stone and the closeness with which they are packed away within a confined space, standing at every conceivable angle to one another and connected by staircases leading up and down and bridges thrown across in all directions (Tozer 1881:437–438).

The monastery of Soumela … now contains 12 monks … The outer wall [of the cavern church] is covered with frescoes of scriptural and religious subjects, but they have been sadly defaced … by Greeks … In front of the church hangs a large wooden semantron or sounding board and close by is a newly built and painted bell-tower, with a dome, containing five bells. … The interior [of the cave church] is unavoidably very dark and the numerous glass chandeliers that are suspended from the roof, together with some beautiful silver lamps, must be often needed. … Numerous small Byzantine pictures are hung about in various places and parts of the walls are covered with frescoes … At the west end stands an elaborately carved and gilt pulpit, from which the Gospel is read and the iconostasis or alter screen, which faces it, is also richly decorated. Within this, in the sanctuary is kept the great object of veneration for which the monastery is famous—a small picture of the Virgin … In consequence of its age and the smoke from the tapers of innumerable devotees, hardly anything more than the old wood on which it is painted is visible; but it is in great reputation amongst Mahometans as well as Christians, for this Madonna delivers her votaries without respect of creed from plagues of locusts and Turkish women are accustomed to visit her shrine in order to obtain relief from sickness and barrenness (Tozer 1881:439–442).

Another manuscript of considerable interest, which is also preserved within the church, is the firman of Mahomet II, by which he granted his protection to the monastery. … with it are a number of similar firmans of later sultans, granting the monks immunity from taxation. In the present days of Ottoman bankruptcy no such privileges are allowed and consequently the present occupants … have to pay taxes like other subjects of the Porte (Tozer 1881:443–444).

It remains to speak of the library. It was located in a stone chamber built high up against the rock face with no means of access to the door. A ladder was used to climb to gain entry to the door with the required key. We found, alas a small dark chamber with one unglazed window, so that, what with the humid atmosphere without and the cold rock behind, the place could not fail to be damp; and the books were piled on one another in the utmost confusion. The monk advised him that they had built a new library but the books had not been moved there as yet. … During the afternoon of the day following our arrival, we sauntered down the zigzag path that leads to the foot of the great cliff and thence through delightful glades to the valley far below … It appeared to us one of the loveliest spots we had ever seen and an ideal resting-place for tired wanderers (Tozer 1881:445–446).

Sergei Mintslov

The following account is an extract from Sergei Rudol’fovich Mintslov’s (1870–1933) visit to Soumela from McCaskie (2022). Mintslov was a Russian army officer and author who was assigned in 1916 to its occupation forces in Trabzon, north-eastern Anatolia. His experiences before, during and after this assignment were captured in diary form in Mintslov (1923). He includes a short stay at the Soumela monastery. The following translated extract from Russian to English by Russell McCaskie is taken from Mintslov’s entry for 27 August 1916. It describes his journey to Soumela with his family and the Greek Orthodox metropolitan of Rhodopolis, Kirillos.

In the morning of the 24th we went by car to Cevizlik.[5] The day before, I had already sent notice to Livera[6] to metropolitan Kirillos to advise him about our arrival. … the horses brought us to the village of Livera – the summer residence of the Rhodopolis metropolitan … In the morning, after a hearty snack and tea we all, including the metropolitan, got on our horses and set off further – to the Soumela monastery … The metropolitan’s guard walked in front armed with an English magazine and a huge quantity of bullets on belts.

… finally in a glade, the blackened walls of a burned out and damaged building appeared. The ravine ended; ahead stood a high forested ridge furrowed by cliffs. The metropolitan stopped and got off his horse. ‘We’ve arrived’, he announced smiling, indicating somewhere higher up. I glanced in that direction and froze. Our ravine turned sharply right and the roaring and booming river jumped over gigantic rocks washing the steep mountain which was propping up the sky itself. At some immeasurable height, up to where only eagles could fly, the long white buildings of the Soumela Monastery were stuck to the sheer rocky precipice.

… the monastery was now hidden from us by a thicket of trees, now suddenly showed itself in all its incredible beauty. … the completely vertical side of a reddish cliff rose further ahead; stuck to it on the right, long and rather steep stairs led off

… We went up the medieval stairway and came to a very small quadrangle; a small bell hung from the gate; a wall rose in front of us and the reddish walls of a church, painted from top to bottom with ancient frescoes looked out at us through an entrance arch.

The gatekeeper struck the bell and in response, small bells from behind the wall began to chime to meet the metropolitan … 75 steps of a second staircase led down to a long open back gallery of monastery buildings; we found ourselves in the monastery yard paved with stones; before us above the church and white bell-tower hung the dark arch of a gigantic cave in the cliff. A large building housing the monastery’s cells and rooms, right on the very edge of the precipice, fenced off the yard like a wall. The number of rooms for new arrivals bespeaks their size – there are 18 of them.

They took us to the largest; several soft divans and armchairs were against its walls; the floor was covered in a luxurious carpet. With some pleasure, we sat down to rest after our long and difficult journey; taking a seat on the opposite wall was the metropolitan, abbot and the monastery librarian – Father Anfim … In the Easter week [April 1916] of this year, several Turkish soldiers turned up at the entrance gate and demanded entry. They were refused. … The monks hid whatever they could and that night, they themselves ran from the monastery down the mountains paths and stole into Livera to the metropolitan.

The Turks turned up at the monastery the next day … The detachment installed itself in the monastery and stayed for two months until Russian forces approached. … they took only silver and especially expensive carpets from the monastery; everything remaining – carpets, furniture and the valuable library – all remained untouched. They did, however, take one official document – a most ancient text of some sultan – from the library. They … ruined absolutely nothing. The walls of the cave cathedral, painted with frescoes, were covered in silver; they pulled this off but did not touch the valuable gold decorative metal plate on the most holy venerated icon of the Holy Mother … The Turks also seized all the monastery’s utensils …

The small church, cave and snug little courtyard in front of it leads the visitor to the first years of Christendom. In the church, a small altar is separated from the worshippers by a low iconostasis and has neither a pulpit nor a side door …

Unfortunately, the external wooden frescoes on the wall and altar ledge of the cathedral have all been covered and spoiled by inscriptions, made by the knives of visitors. I thought that such abundance of stupidity happened only with us in Rus: it turns out there are plenty of Greeks who do this too!

In two places near the church, springs have broken through the rock face and only their murmur breaks the silence of the yard.

… A balcony with a canopy leaning on columns of white stone stretched along the whole upper floor of the hostel building. I know nothing which can compare to the raw beauty of the view from this balcony!

… In the morning, having looked around the library containing not a few ancient manuscripts and signed the visitor’s honour book which had been started as early as the 1660s we, accompanied by all of the very few monks, started down the staircase on our way back.

Again, the soft quiet peal of the bells farewelled us. From the upper courtyard, we looked for the last time at the little church hidden in the dark part of the cave and began to descend to the horses which were waiting for us.

Near them, we farewelled the monks and leading our horses by the reins, it was like we sank into the fresh green forest. Now and then, the monastery could be seen hanging in the air through the shafts of light through the tree tops; after the bridge, we got into our saddles and the marvellous fairy tale of the power of the human spirit, having flown beyond the clouds, disappeared around a turn.

David Talbot Rice

Professor David Talbot Rice (1902–1972) was an English art historian. He noted in 1929 that Soumela was an immense structure, which crouches under a giant ledge of rock some 900 feet above a rushing stream, in the most astounding position imaginable. The monastery beared witness to the skill of its builders. The ceilings have been torn down and the floors torn up. The rooms are now fully exposed to the severity of the weather (Plate 4) (Talbot Rice 1929–1930:73, 74).

The only entrance is at the south end of the rectangle. It consists of a small door about 1.7 metres high and 80 centimetres wide, at the top of a long narrow stair. … Within the door are living rooms for the porter, with a small upper court some two metres below them, to the north. The main court lies some fifteen metres below this … It is reached by a long stair, bordered on its eastern side by the main living and guest rooms which date from 1860. These continue along the east side of the main court, on the west of which is the rock cut church, a few minor buildings and a small chapel. To the north-east are further living rooms, built in among which are three minor chapels.

To the west of the main court, close to the church, stands the phiale or water fountain, open at the top to catch a perpetual drip from the rock which overhangs a hundred feet above. In a corresponding position, to the north of the church stood the bell tower, but only the lower story of this now remains. To the north of the court the outside buildings again continue for some thirty five metres along a narrower portion of the ledge, their backs being separated from the rock by nothing more than a narrow verandah (Talbot Rice 1929–1930:75).

The main church is in two parts, a large irregular cavern cut out of the rock and closed at the eastern end by a wall and a small sanctuary built out of this wall, in the form of an elongated apse. … On the north side of the church is a cavern, separated from it by a wall only … on the south side is a small chapel. This is hewn entirely out of the rock … Directly in front of the church to the east, but on a lower level, is a small chapel, the western portion of which now serves as a passage. … Under the bell tower to the north of the main church is a second small chapel, containing frescoes (Talbot Rice 1929–1930:76).

Conclusion

The common theme of the descriptions by these foreign visitors from 1701 to 1929 of the Soumela monastery is absolute awe of its beauty and its surrounds. For those of us who have visited the monastery can only but agree with these historical observations. Despite the grandeur of the site, we should not forget the harsh conditions, especially during the colder months, in which these dedicated monks lived in the monastery.

More recently, after years of renovations, the Soumela monastery was re-opened to tourists.

Acknowledgements

I warmly thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

Bryer AAM and Winfield D (1970) ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes—part 3’, Archeion Pontou, [Archives of Pontos], 30:228–375.

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I & II, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Chrysanthos (1933) ‘H Eκκλησια Τραπεζουντος’, (in Katharevousa Greek), [The church of Trabzon] Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], iv-v, Athens.

Holy Apostles Convent (1991) The lives of the monastery builders of Soumela, (a translation from the Greek of The Great Synaxaristes of the Orthodox church), pamphlet no. 2, Holy Apostles Convent, Buena Vista, Colorado, USA.

Lowry HW (1991) ‘The fate of Byzantine monastic properties under the Ottomans: examples from Mount Athos, Limnos & Trabzon’, Manzikert to Lepanto: the Byzantine world and the Turks, 1071–1571,:275–311, Papers given at the nineteenth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, March 1985, Bryer A and Ursinus M (eds) (1991), Adolf M Hakkert, Amsterdam.

McCaskie R (2022) ‘Reflections on the Soumela monastery in summer 1916’, at:www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/articles/807-reflections-on-the-soumela-monastery-in-summer-1916

Mintslov SR (1923) Trapezondskaia epopeia, (unpublished translation from Russian to English by R McCaskie), Sibirskoe Knigoizdatel’stvo, Berlin.

Nuhoglu Y, Var M, Koçak E, Uslu H and Demir H (2017) ‘In situ investigation of the biodeteriorative microorganisms lived on stone surfaces of the Sumela Monastery (Trabzon, Turkey)’, Journal of Environmental & Analytical Toxicology, 7(5):10pp.

Talbot Rice D (1929–1930) ‘Notice on some religious buildings in the city and vilayet of Trebizond’, Byzantion, 5(1):47–81.

Tanimanidis SP (2020) Historical account of the holy icon and the monastery of Panagia Sumela, [translated into English by P Papadopoulou], publisher not stated, place of publication not stated, 256pp.

Tournefort JP de (1741) A voyage into the Levant, vol. III, letter v, (translated from French to English by J Ozell), originally published in 1717, London.

Tozer HF (1881) Turkish Armenia and eastern Asia Minor, Longmans Green and Co, London.

[1] The Rhodopolis metropolitanate was south of the larger Trabzon Greek Orthodox metropolitanate.

[2] Words within ‘[ ]’ within a reference signify the author’s own words.

[3] For more details on Soumela see the author’s article at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/pontus/news/795-the-soumela-monastery-pontos-2

[4] Talbot Rice is his surname.

[5] It is usually called Maçka (pronounced Machka).

[6] Livera is a Christian Greek village in the Maçka region and the seat of the Greek Orthodox metropolitanate of Rhodopolis.